Has France outlived the traditional role of its president?

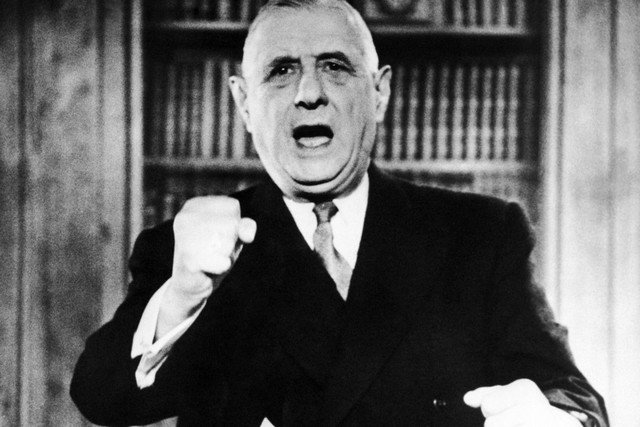

When Charles de Gaulle created the role of president of France almost 60 years ago, the job description was not like other heads of state.

It required someone who could represent the grandeur and spirit of France, at a time when it was recovering from the wounds of occupation in the Second World War and going through the trauma of the Algerian war of independence.

In brief, the presidency of the French Fifth Republic was tailor-made for the general himself – someone who could claim to be above politics and take the difficult decision to decolonize Algeria, which until then had been considered part of France. That step almost brought France to civil war.

The general's legacy

The general's legacy has weighed on the shoulders of his successors. The intellectual brilliance of Valery Giscard d'Estaing carried him through one seven-year term, and the devious Francois Mitterand managed in the course of two terms to keep secret the truth about his declining health and his extra-marital family.

Later presidents, serving in times of less deferential media, have had less success, culminating in the fate of the outgoing socialist president Francois Hollande, who has been so unpopular that he did not run for a second term. Most of Europe reacted with relief when the independent centrist Emmanuel Macron came top of the first round of voting in the presidential election, pushing the far-right leader Marine Le Pen into second place. But a question mark remains: is the job of president of the French Fifth Republic too big for any politician today?

In de Gaulle's eyes, the victory of a suitably grand president – such as he became – should be followed by a parliamentary landslide in sympathy, even if the head of state did not formally lead a political party. That was the meaning of representing the “spirit of France”.

Today the spirit of the country is angry and suspicious of politicians: in the first round, 41 per cent of voters cast their ballots for anti-establishment figures, while Macron won support by appearing as a fresh, new face at the head of a recently minted political movement. This is something of a triumph of image over reality – he is a product of the elite, having served as a Rothschild's banker and in the key position of economy minister in the discredited socialist government of president Hollande.

His great advantage is not being Le Pen. With his charm and financial experience he was able to collect the votes of those who still believe in a strong European Union, in global trading links and open borders – the optimists as opposed to the pessimists in the anti-Muslim, Eurosceptic Le Pen camp. With an electorate that is only weakly committed to him, Macron still faces a high hurdle in motivating the voters to push him over the line in the second round of voting on May 7.

But even in the event of victory for Macron – and he is the clear favorite – he may still find himself short of a majority in parliament when the legislative elections take place in June. His political movement, En Marche!, is barely a year old and has no members of the National Assembly. In a spirit worthy of the general himself, Macron hopes that many sitting deputies in the National Assembly will abandon their party affiliation and defect to his movement. They seem unlikely to do so. The problem here is that a new president who cannot summon a reliable parliamentary majority may become a lame duck on day one. The powerful presidency envisaged by Gen de Gaulle can be reduced to ribbon cutting.

Macron is clearly no pushover. But the brutal truth is that he has climbed to prominence on the rubble of the two-party system that has kept French politics stable since 1958. If the politics of left and right reasserts itself, then Macron may find himself squeezed into impotence between these two poles. If the party system remains weak, then his future would be an unending scrabble for votes to get his program through parliament.

The Fifth Republic

The Fifth Republic has been here before. In 1997, the conservative president Jacques Chirac called an early election to try to increase his parliamentary majority, and found himself facing a socialist-dominated parliament. He was obliged to name the socialist Lionel Jospin as prime minister, ceding to him leadership in domestic policy.

Unlike in the United States, where conflict between the presidency and Congress is built into the constitution, in France, with a long tradition of a significant state role in the economy, the deadlock of cohabitation is a recipe for stagnation.

Macron is labelled a progressive, but this means different things to different audiences. He believes in liberalizing the French economy by making it easier to hire and fire. Unemployment for those under 25 in France is now around 25 per cent compared with about 7 per cent in Germany. But young people find little solace in existing measures – including those favored by Macron – which have meant that more than half of young people in work are perpetually cycling through short-term contracts, deprived of the stable employment enjoyed by their parents.

In a country with a tradition of viewing Anglo-American finance-based capitalism as a threat to France's way of life, Macron has told the voters that “modernity is disruptive” and they have to get used to it. This is the antithesis of Le Pen's diatribes against “wild globalization” which have struck a chord with both young and old in France. Macron's greatest challenge is likely to be after his election. If he proves unable to address the deep-seated problems facing France and the European Union, it may turn out to be the last gasp for de Gaulle's view of the president of the republic as a towering figure behind whom the political class ought to rally.

(Source: The National)

Leave a Comment